I got an email the other day for an academic conference session called Intimate Ethnographies in Multispecies Lifeworlds. This important discussion is due to be held next spring at the American Association of Geographers conference in Denver, Colorado, and is being organised by Katie Gillespie and Yamini Narayanan. ‘What on earth is that?’, some of you ask, including me. OK, so let us break it down. Ethnography is when you study a population through living with them. And intimate ethnographies must be when you do that in very close quarters. So, for example, an intimate ethnography of a ‘tribe’ or ‘subculture’ might involve studying them through living with them, perhaps living in the same house, living in the same room even, and conducting their daily routines with them, as they do. OK, next- multispecies lifeworlds– here is the idea that we are studying the lives, experiences, thoughts and feelings – ways of being- of not just humans, but other species. And not just one species, but more than one, and our coexistence.

I read on with interest. The session organisers show a particular interest in auto-ethnography. Which, yes, you have it, means an ethnography of yourself, or your life(world). ‘Ooh’, I thought excitedly, ‘that’s what I am doing’. I always felt I could not help but be a sociologist in my own life. This is why I started to blog. I had not thought of my writing as auto-ethnographic before, but it is slowly becoming that way.

Then I saw the phrase ‘attention to uneven power structures’ and I thought again, that’s my interest. In any given situation I study, I am always interested in who has power and who does not, and how that plays out. Katie and Yamini go on to claim that ‘Centering lives lived in close relation, in multispecies lifeworlds, allows for a politicization of these relationships and the contexts in which they unfold’. I am aware that almost all of our perspectives give precedence and power to humans over any other animals, as a base assumption. Animals are considered to be secondary, second-class, ‘sub’ human. The way we construct knowledge- or the way we think about, and understand, ourselves and our time on this planet -is inherently ‘species-ist.’ So, these geographers call for us to think more about humans’ relationship, coexistence, symbiosis with the animal world, and the multiple species in it, and to apply a political lens to this study. They invite us to ask: who is the ‘underdog’ here? What are the ‘power structures’? How are they uneven or biased in favour of humans? What are the consequences of this? How can we think differently about this?

One of the specific questions they ask researchers to tackle is:

– What might an intimate ethnography look like with those animals closest to us—for instance, how might we think about ethnographies of those with whom we share our lives, our homes?

Well, here goes.

An intimate ethnography of human-insect-vanlife-life-worlds

Living in a campervan for months on end, moving from place to place, means having a very different relationship with the natural environment (and the creatures in it) than you do living in a house. This experience has made me think a lot, specifically, about the insect world and our relationship to it, because, living in a van in the woods; on the beach; in a field; up a mountain; by a stream, we come into contact with various, and multiple, insects on a regular basis. When I lived and worked in London, when I reflect back on it, I rarely saw or thought about an insect*.

Last winter I read a feature article in the New York Times called The Insect Apocalypse Is Here. This piece summarised scientists’ incredibly worrying hypotheses that overall insect numbers are decreasing rapidly, year on year, with potentially apocalyptic consequences. Reading this article, has also informed my shifting relationship with insects. The journalist invites us to cast our minds back to when we were young (presumably assuming a readership born in the 1970s and ’80s), where he tells the story of a science teacher who recalls when he was a child, driving (and cycling) through the summer countryside in his home town in Denmark and the number of bugs striking the windshield (or his face!) was in the thousands. But today, that same experience, might be merely tens of insects. If that. If I cast my mind back, when I was a kid, living in a house in a semi-rural area of Southern England, this used to involve co-existing, to some extent, with various insects. In the autumn the spiders would come in. Big ones, small ones, hairy ones, ginger ones. There was always one in the bath, or one in the corner of the room. In the summer there were the flies that would invariably bother you in the kitchen; when you were trying to cook; the moths that would come in around the porch light at dusk; the ‘daddy long legs’ who would dive bomb you in the hall way; the dragon flies around the pond. Towards the end of my time in London- a large but relatively green metropolis- when I think about it, I rarely encountered insects in my home (except the bed bugs that had been ‘imported from India’, but that is another story all together).

Living in a van, however, it was necessary to coexist with various insect populations. Everywhere we traveled, there would always be some kind of insect population making themselves known to us, getting in our space, as we got in theirs. Interestingly we tended to be aware of one type of insect species at a time, as if they had different geographies, or they took it in turns to taunt us. We had bees in the mountains of Fethiye; mosquitos on the beach on the Albanian Riviera; beetles in the forest in Alanya; locusts in the grasslands in Halkidiki; sandfleas at the harbour of Andriake; flies in the farmlands in Urfa; scorpions in the Sahara dessert. As we failed to install any mosquito screens in our campervan and the temperature inside in summer was often 40 degrees or more, the open windows and roof vents meant there was no getting away from the insects. We had to at least try to get along with them. In the beginning we would spray the campervan with insecticide (indeed some campsites we stayed on sprayed the entire campsite with insecticide), but we soon learnt this was futile: it didn’t seem to remove the insects, only kill some of them and then more would appear. So we realised this was unsustainable, not to say inhumane, and we began to try to tolerate them.

Another thing I became very aware of -in addition to the different insect geographies- was that they tended to have quite discernible daily rhythms too. Cicadas would sing all day, and then would instantly go to sleep, or just stop talking, at dusk**; flies would be attracted by food so would come at meal times; bees by water when we were washing; mosquitoes would come at dusk, feed from us over the period of about an hour, and then retreat, leaving us in peace for the night. Only when there was a plague of mosquitoes (i.e. problematically large numbers) did they continue to bother us through the night. Well, of course, I guess it makes sense: if there were more of them, then it would take longer for each to get their turn to feed. I began to change my attitude towards insects, as I began to have a relationship with them, as I began to understand them, and their needs. I read that mosquitoes take your blood to feed their babies, and I thought ‘oh well, in that case, fair enough’. Wouldn’t you do anything to feed your baby? We tried to avoid being bitten, through natural means- covering up with long clothing at dusk; covering my son’s bed with netting; burning citronella; sleeping in the path of a fan, and if there was a real plague of them we would cover ourselves in DEET to repel the worst of them. However, as time went on, I began to tell myself to just let them be, let them do their thing, let them feed. Just try to ignore the itch. It would be gone or replaced by a different itch in a few days. This was just the cycle of life.

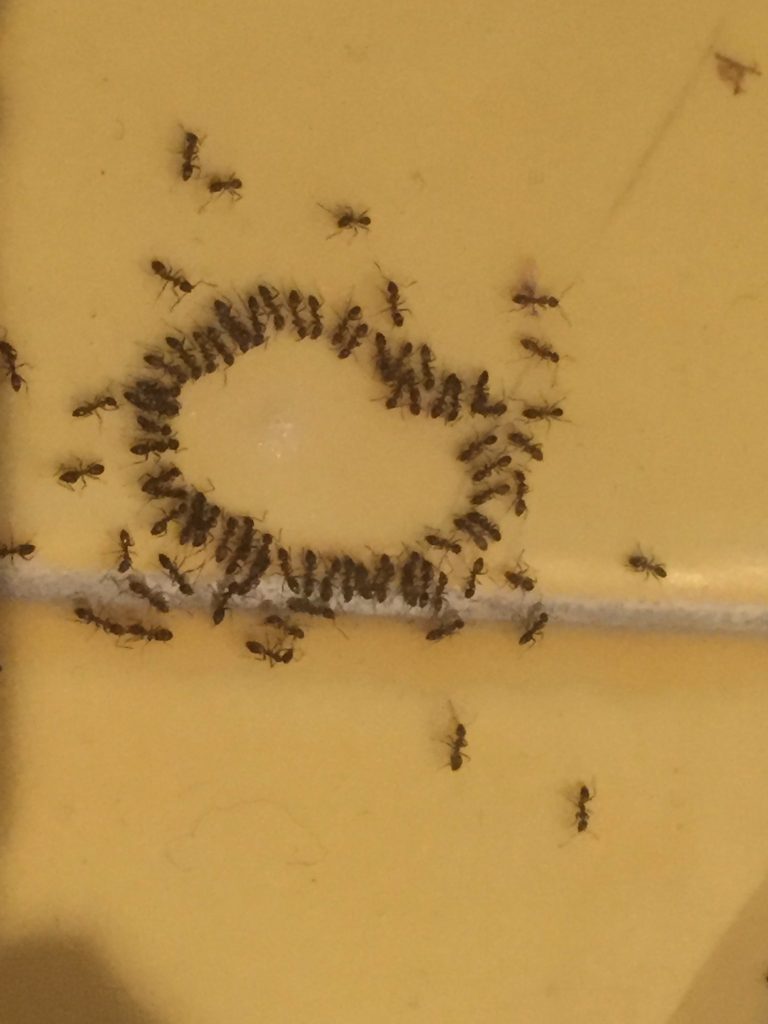

The ants of Andalucia

When we were in Spain it rained. And rained. And an extended family of ants congregated in our shower. Our first reaction was horror and we wanted rid of them- they were in our space. But my partner, who is Muslim, said ‘in Islam you are not supposed to kill ants’. So we didn’t. We soon realised they came in when it was raining hard, they had their meeting (literally convening in a circle) and then when the rain stopped they would go back outside, and we were able to shower. Phew. This brings a new meaning to flat sharing.

The Fethiye bees

That is not to say that I was not challenged by the presence of some insects on various occasions. Flying beetles dive-bombing through the roof lights at dusk was quite panic-making, and we were not prepared to share our space with these blighters. The ‘Fethiye bees’ was another strange encounter. When traveling in southern Turkey we parked at an idyllic spot in the forest in the mountains above Butterfly Valley (interestingly, but perhaps unsurprisingly, said to be lacking in butterflies now). We planned to cook dinner while our son played outside. I went outside to do some washing up in a bucket while my partner was cooking, but by the time I had finished the washing up I had about ten bees around me. When I finished the washing up they swarmed the tap, the washing up sponge and the pile of wet gravel where I had poured my washing up water. ‘OK, they are just thirsty’ I said to myself. But gradually they started to surround the campervan, sitting on the van and coming inside. They weren’t just thirsty, they were watching us. Then my son came inside. This was strange because he never came inside voluntarily. When I asked him why he had come inside he said dismissively: ‘oh, just too many bees’. He had left all his toys on the mound where he was playing and when I went to collect them, the toys were crawling with bees. I looked around. The bees were nowhere else to be seen. Only on our belongings. This was the point at which I said ‘OK we are leaving.’ The way in which they were surrounding us, watching us, taking interest in us, marked unusual behaviour for me. This seemed bizarre behaviour for bees: usually we coexist, but they show little interest in us. Perhaps we had disturbed their nest? But they were not stinging us, not threatening, just showing too much interest. This was too eerie. We packed up and drove off, driving fifty miles down the mountain and out of the forest into an urbanised area. That was better: just species like us here.

The angry locust

This takes me to my last story, or encounter: the angry locust***. In Greece we spent nearly a month camping in abandoned campsites on the peninsula of Halkidiki. The economic downturn had obviously affected tourism and holiday-making and more than one campsite had closed-down in this region. We parked up on the beach near Sikia, in one such abandoned campsite, in the long, wild grass, under the shade of a tree and started to assemble our camp. We were aware of the noise of ‘cicadas’, in the long grass, which was a noise we were accustomed to. However as we settled in our camp we realised it wasn’t multiple ‘locust’ sounds coming from all around, but the noise was localised: it was coming from only one patch of grass. It was incredibly loud, and incessant and very close to our camp. We peered into the long grass and could not believe our eyes. The creature we saw was almost the size of a small rodent. But it was an insect. And it seemed to be shouting at the top of its ‘voice’. When we peered closer it would stop, but as soon as we moved away it started again. We sat for a while outside, but he disturbed our peace. We decided to go inside and have a nap, but the noise continued and seemed to get closer. We couldn’t sleep. Then I thought I heard another sound, this time coming from the opposite side of the van. I went out to investigate and indeed there seemed to be a response of sorts, coming from long grass the other side of the van. ‘I think we are in his patch’. I said. ‘We are parked in the way between him and his lady, and he’s not happy’. As the noise got louder and angrier, again, we agreed to move. We packed up the van and drove about fifty yards away to another pitch and parked up. We then walked slowly and quietly back to the pitch with the locust and indeed the noise had stopped. Whatever the matter was, he was quiet now. One nil to the locust.

All power to the insects

These are trivial stories of encounters with insects but I want to draw attention to the power structures, as Katie and Yamini ask us to do. For all-too-long we humans have wielded power over insects (and indeed most other species), with little concern for their welfare, or even concern for how much we need them. As the article about the insect apocalypse points out, we are dependent on insect populations to pollinate our crops, to process our waste, as a food source for other animals. Without them we will starve and be neck deep in shit. But our attitude for far too long has been: Not In My Back Yard. As we swat that swatter; spray that Raid; pump that insecticide; jet that pesticide; spread that Rose Clear; shake that ant power, little by little, we contribute to this holocaust. Van-life has fundamentally changed that relationship for me. I draw the line at flying beetles in my hair, but other than that, live and let live. I learned to live with insects, to the extent that, now I am in a house in the city again, I miss them. Not only should we learn to coexist with insects, but, as with the bees; the mosquitoes; the ants; the angry (or horny?) locust in my stories, we should be curbing and adapting our lives, our behaviour around theirs: we should be allowing them to take the stage. Because one day we might miss them.

———————

Insect Trivia:

Crickets, locusts, grasshoppers and cicada: what is the difference?

Locusts are a type of grasshopper, both categorised as ‘Acridoidea family’ in the order ‘Orthoptera’. Crickets are also of the Orthoptera order, but crickets are typically wingless, and they are omnivorous: eating plants, smaller insects and larvae. Locusts and grasshoppers look similar to each other, they both have wings, and are both herbivores but locusts differ from grasshoppers in their ability to swarm. These insects make a sound by rubbing their wings together and this is called stridulation. Cicadas on the other hand, are ‘true bugs’ from the order Hemiptera, they are dark, stout insects with large heads and transparent wings. They look more like a beetle. They come in two major variations: annual cicadas, and periodical cicadas. Periodical cicadas (only sited in North America) are often commonly referred to as the ’17 year locust.’ They spend 13 to 17 years as ‘nymphs’ living under ground, feeding from the juices of plant roots, before emerging- in number- in spring, when the soil reaches exactly 64 degrees Fahrenheit, when they climb up trees, shed their brown nymph skin and emerge as a cicada (most commonly black, with red eyes and orange wing veins). The male cicadas, the loudest insect around, then ‘sing’ by producing a sound from a pair of built-in drums called tymbals at the base of their abdomens. The females are attracted by the sound and after mating the females lay eggs burrowed in the twigs of the tree, before dying. The eggs then fall to the ground and hatch into nymphs who burrow into the ground, where they will then live for around 17 years. There is nothing trivial about that.

Photographs featured:

Feature photographs are courtesy of Penny Metal and Naomi Adams. Penny Metal is an artist who loves and photographs insects. She has published a book consisting of photographs of the insects of Warwick Gardens, a small park in Peckham ,South London. You can see more of her photos and buy the book here. Naomi Adams is an artist and illustrator. Her relief pictures of bugs and beetles made from minute, found-objects such as beads, earrings and clock parts, can be bought here.

Footnotes

* Such is the rarity, that the beauty of the urban insect has attracted the attention of South London artist and photographer Penny Metal, who has published a book of photographs on these creatures, and our encounters with them.

** The sound Cicadas make is actually made by their abdomen not their mouth so technically they are not ‘talking,’ but I am anthropomorphising for dramatic effect.

***After researching, it is most likely it was a Cicada that we saw, not a locust, but humans often confuse the two.